In Book VI of Tutte l’opere d’architettura et prospetiva, Sebastian Serlio opens the text by describing the first dwellings of early humankind. In their combination of branches, clay, and direct excavation into the soil, Serlio sees an emphasis on commodity but a lack of decorum, where commodity signifies comfort and shelter, and decorum refers to a building as a formal and cultural construct. Serlio frames his treatise as a call for harmonizing these two concepts, bringing them into balance. For this reason, the architectural orders are of great importance to Serlio—they are an ornamental articulation that embodies architecture’s capacity to communicate.

Today, the gap between commodity and decorum has only grown wider, as both concepts have been distorted by the economic logic of the market because the buying and selling of space generates a process of valuation which is disassociated from both the material constitution of architecture and from the intersection of buildings and culture. In this context, contemporary designers might strive for simplicity, efficiency, honesty, or functionality, thinking they lend a sense of commodiousness to space, but these expressions are nevertheless an ornament onto an abstract system of development driven by pro forma analyses and returns-on-investments. Design becomes a photogenic appliqué in order to obtain that ubiquitous image with mass appeal, generating dreams and sales.

Today, the gap between commodity and decorum has only grown wider, as both concepts have been distorted by the economic logic of the market because the buying and selling of space generates a process of valuation which is disassociated from both the material constitution of architecture and from the intersection of buildings and culture. In this context, contemporary designers might strive for simplicity, efficiency, honesty, or functionality, thinking they lend a sense of commodiousness to space, but these expressions are nevertheless an ornament onto an abstract system of development driven by pro forma analyses and returns-on-investments. Design becomes a photogenic appliqué in order to obtain that ubiquitous image with mass appeal, generating dreams and sales.

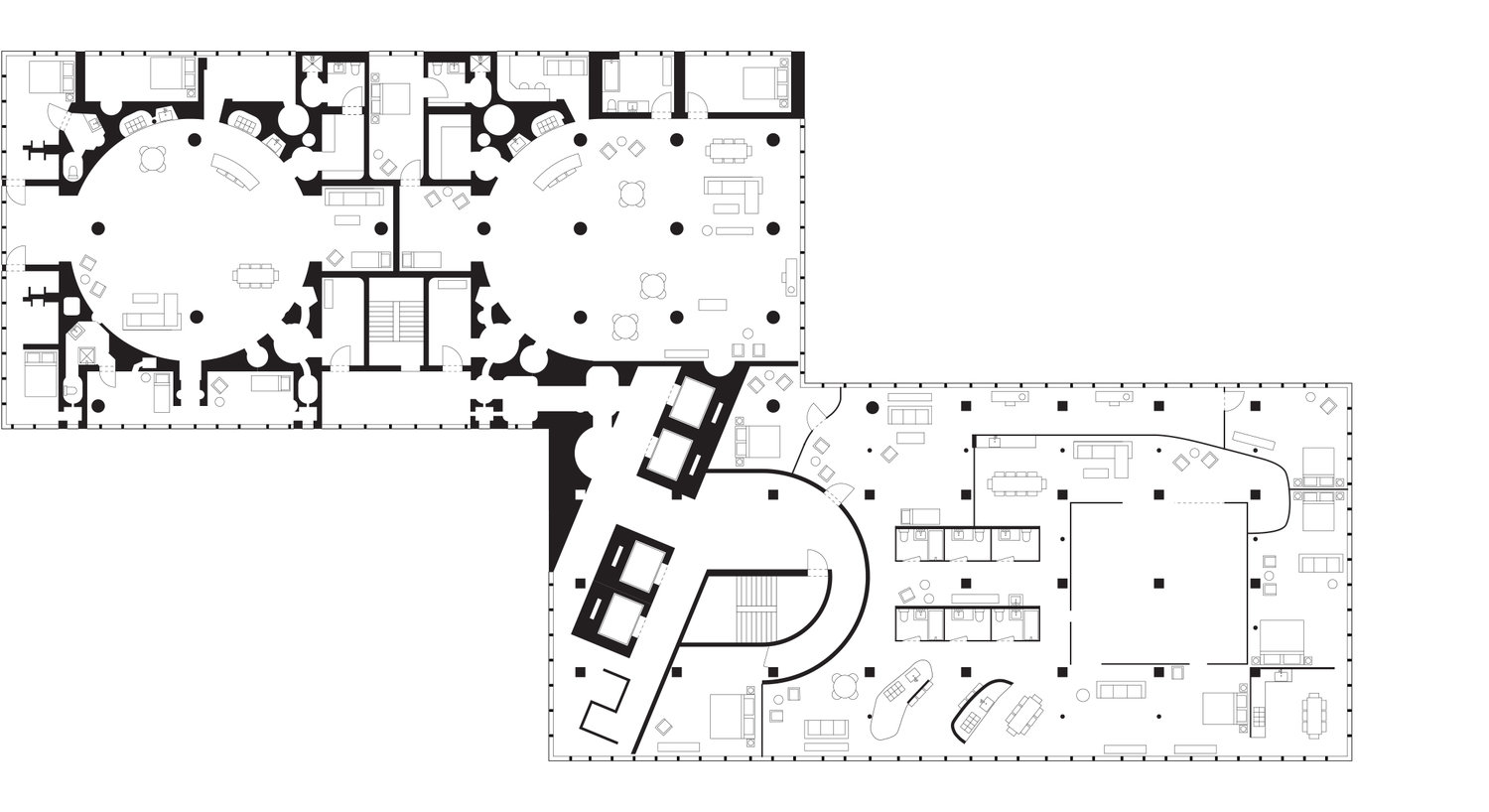

On the left is a plan inspired by Sebastian Serlio’s House of the Exceedingly Illustrious Prince. On the right is a modern free plan inspired by Le Corbusier’s concept of the plan libre. Despite the explicit use of precedent, historical citation and reference are not the intention of this project. The plans from the 16th and early 20th centuries are juxtaposed and framed within One Manhattan Square as a reflection of the current condition of cities. In New York, for instance, we have interiors not unlike the Serlio plan occurring in the pre-war housing of upper Manhattan while the free plan is ubiquitous in new construction. However, Serlio designed for a prince, allowing the orders to signify social hierarchy. The free plan, on the other hand, embodied change in the means of production and introduced space that could be universally common to all. Ironically, their juxtaposition present antithetical paradigms and a contradiction of form, but enclosed within a single envelope, the two plans are theoretically indistinguishable in the current condition generated by market economics in the sense that both are insurmountably unaffordable. As such, Face Value observes the absorption of architecture into the capitalist model. Profit overshadows commodiousness and decorum is considered external to the development process.

By resolving the transition between the plans, essentially, a wall architecture flowing into a column architecture, Face Value reflects the dissolution of difference and the de-signification of design in our current condition. Both plans, in this context, equally operate with a complete lack of decorum, exposing the commodity in its incapacity for dialogue with the former to begin with.

By resolving the transition between the plans, essentially, a wall architecture flowing into a column architecture, Face Value reflects the dissolution of difference and the de-signification of design in our current condition. Both plans, in this context, equally operate with a complete lack of decorum, exposing the commodity in its incapacity for dialogue with the former to begin with.