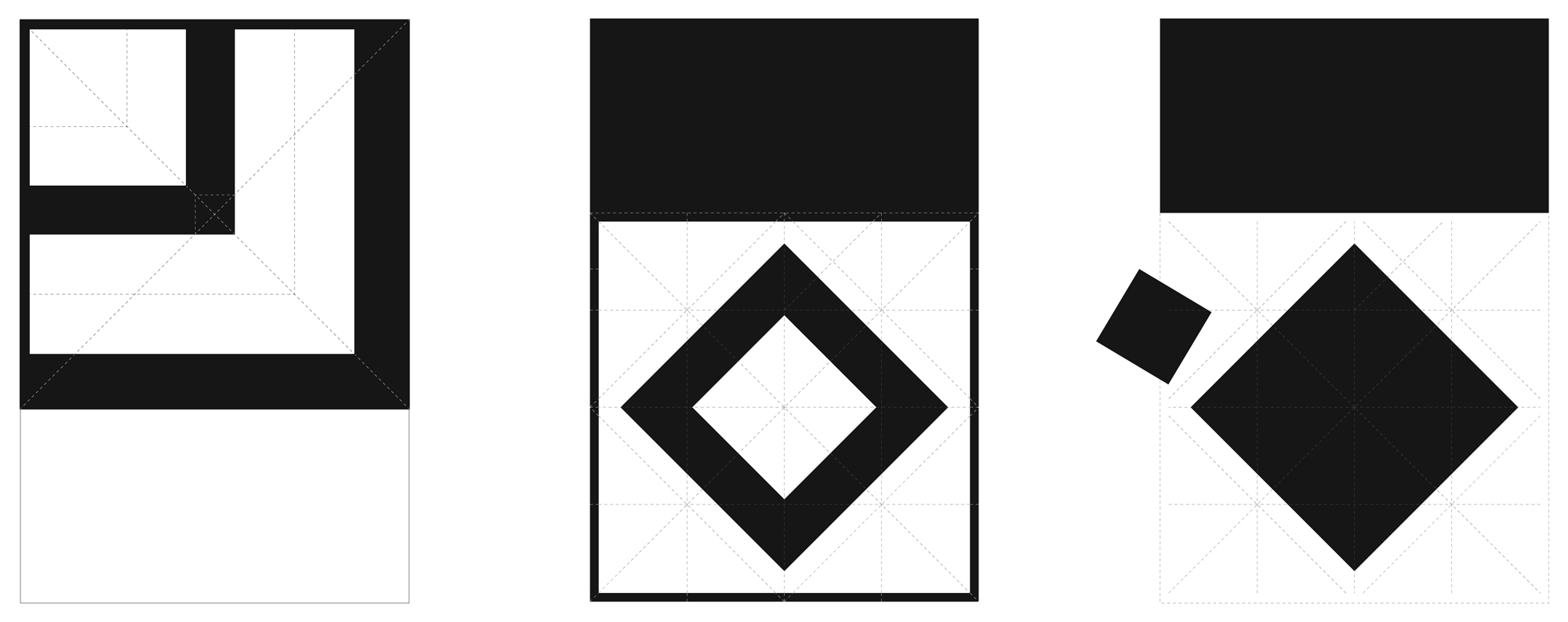

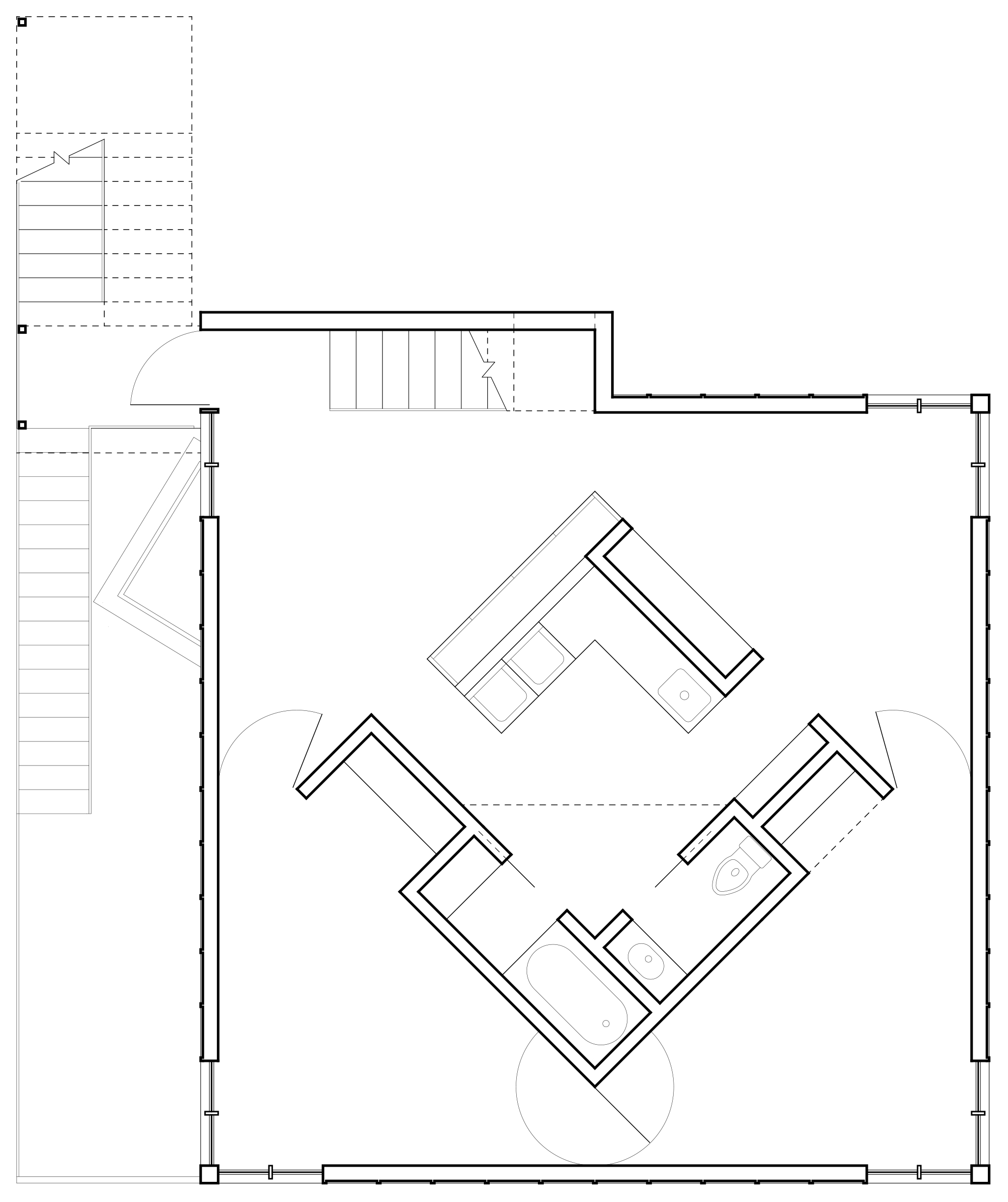

The Stella and Noland paintings previously shown are derived from gridded space—which is not to say that they portray grids, but rather that they come from the flattened, geometricized, structured, and anti-mimetic space of modernist painting. As such, they draw from the duplicity inherent in painted grids, whereby the frame is set into tension by the grid’s implication of infinity. Stella exerts pressure past the edge of the painting. One imagines the cascading bands extending limitlessly, or wrapping up and around to enclose the square in the corner, replicating it outward in endless offsets. The painting is a fragment of cartesian infinity. Noland, on the other hand, exerts pressure between painted figures. The diamond, the circle, and the canvas itself reverberate against each other, producing tension internal to the painting, forgetting the space beyond the frame. These paintings present the possibility of simultaneity in pictorial space. Both material and immaterial, either inward or outward facing, they accommodate tension and contradiction. For this reason, the painted grid is “cheerfully schizophrenic.”(1) In Modernist painting, for the art historian Michael Fried, the tension between Stella and Noland is a matter of opposing forces between the literal shape of the painting—i.e. the shape of the canvas—and the figure painted on its surface, what he calls the depicted shape.(2) With Stella and Noland, the painted figure either follows or fights the frame of the painting itself. Here are the plan diagrams of our house:

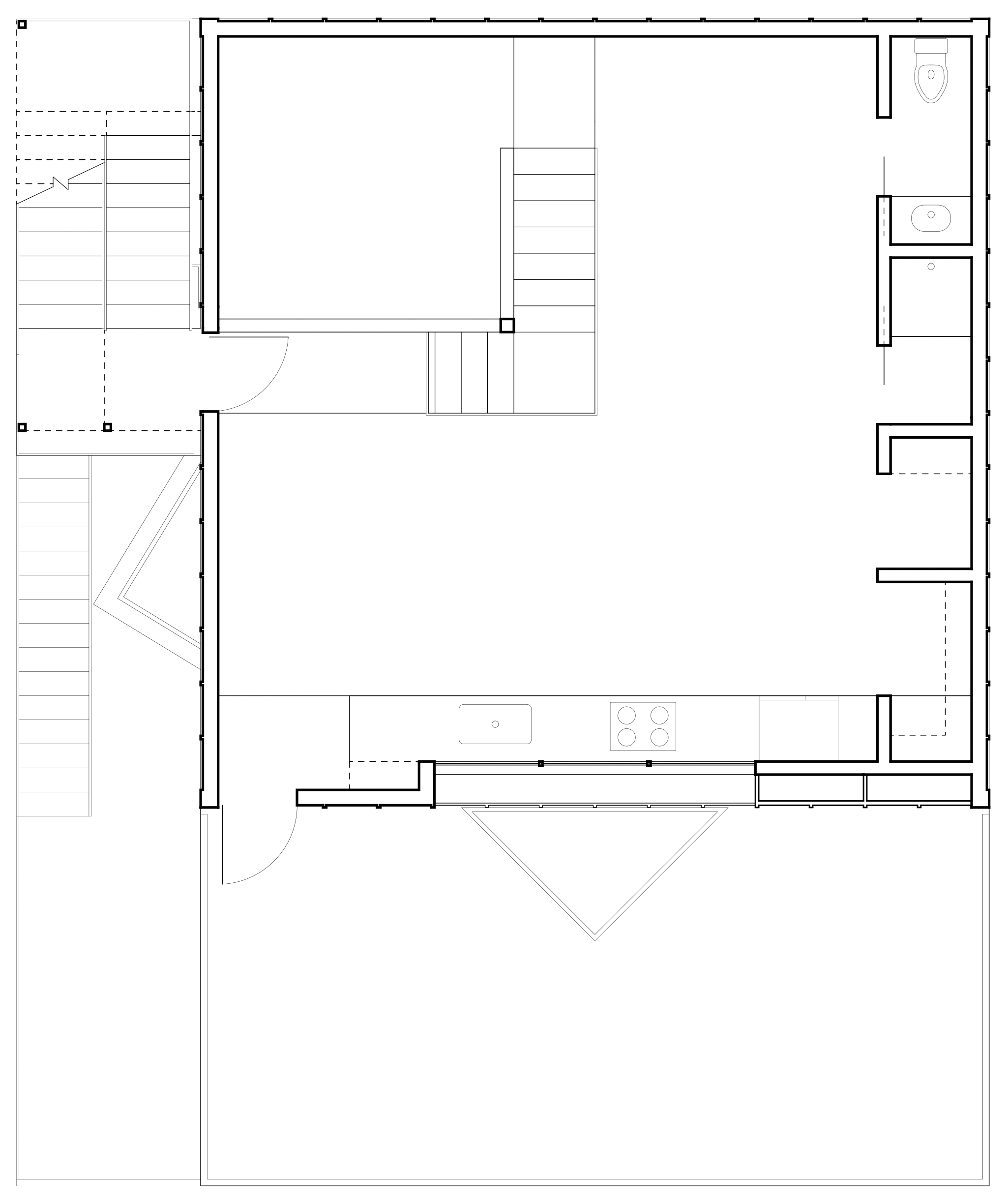

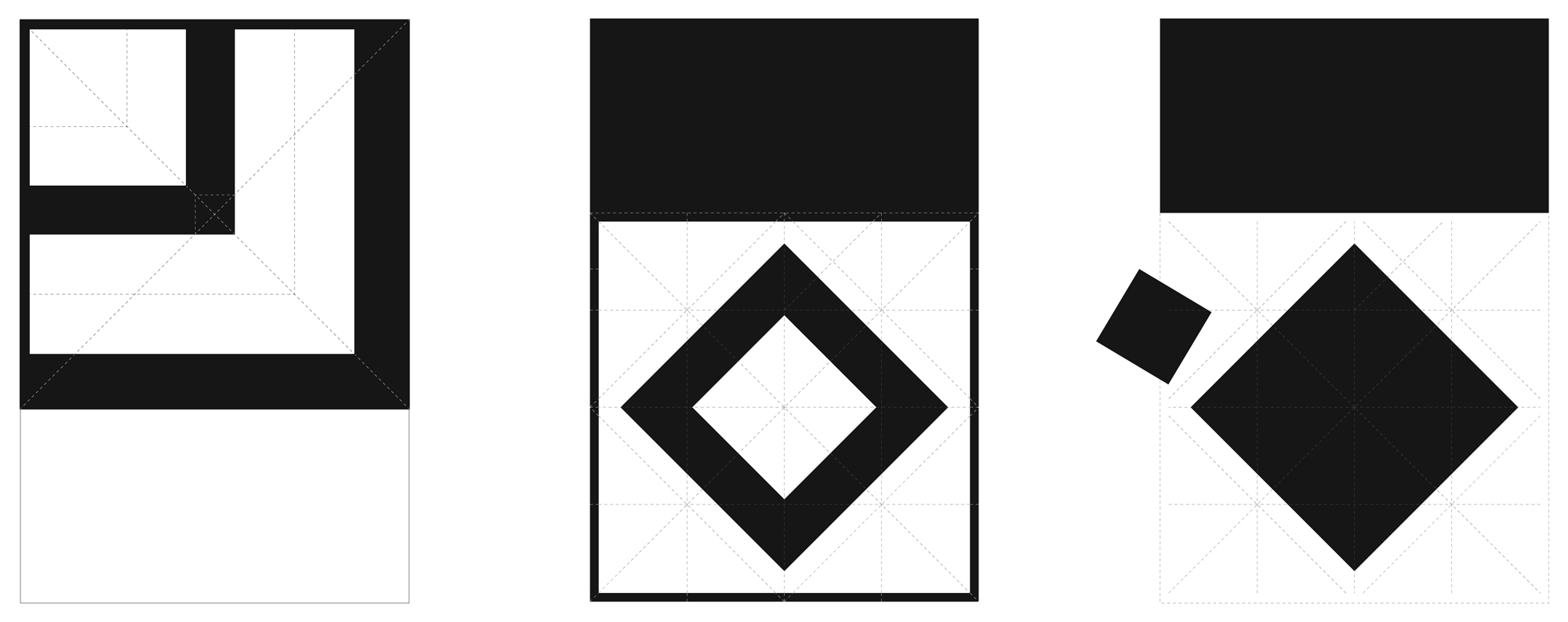

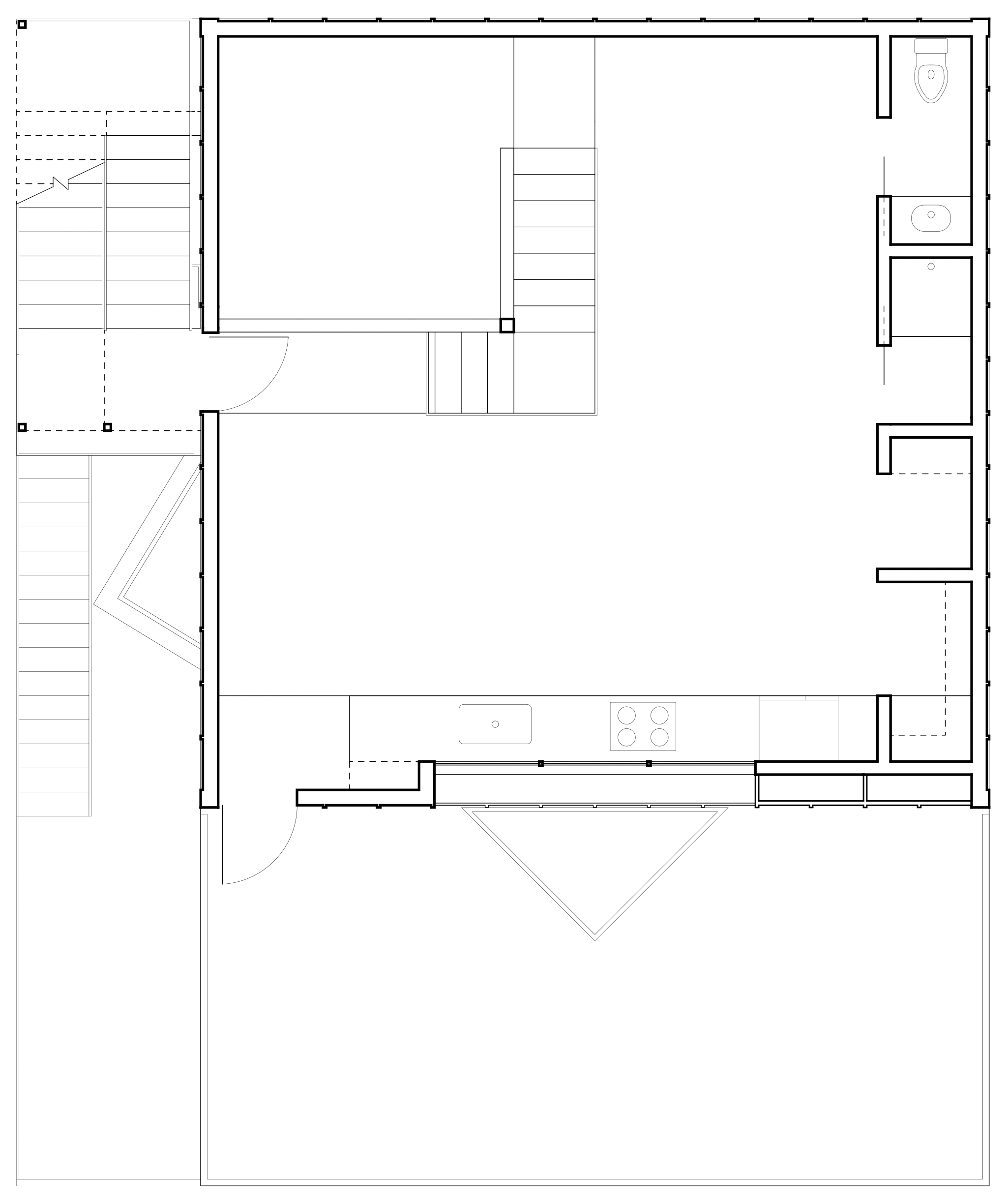

An initial reading of the plan shows the architecture exploiting the tension between literal and depicted shapes. If the literal shape in painting is the canvas and if the canvas is the field of action, then in architecture our literal shape is the outline of the floor plate, across or against which depicted shapes are laid out, either following or fighting the edge. Here, on the ground which is our canvas, both space and human activity are organized. In our upper plan, the formal logic is governed, as in Stella, by the literal shape, whereby L-shaped bands replicate the edge of the square floor plate.

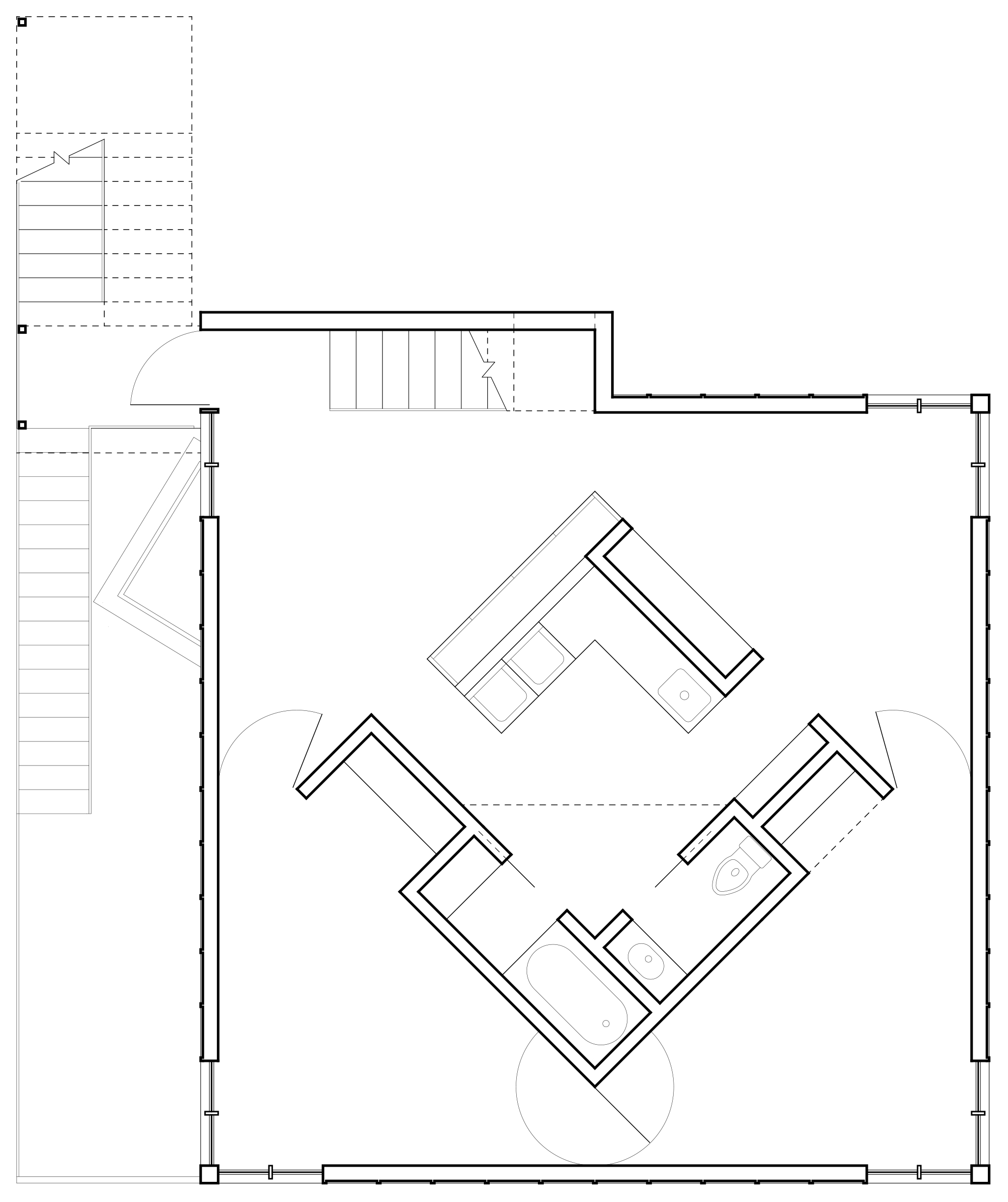

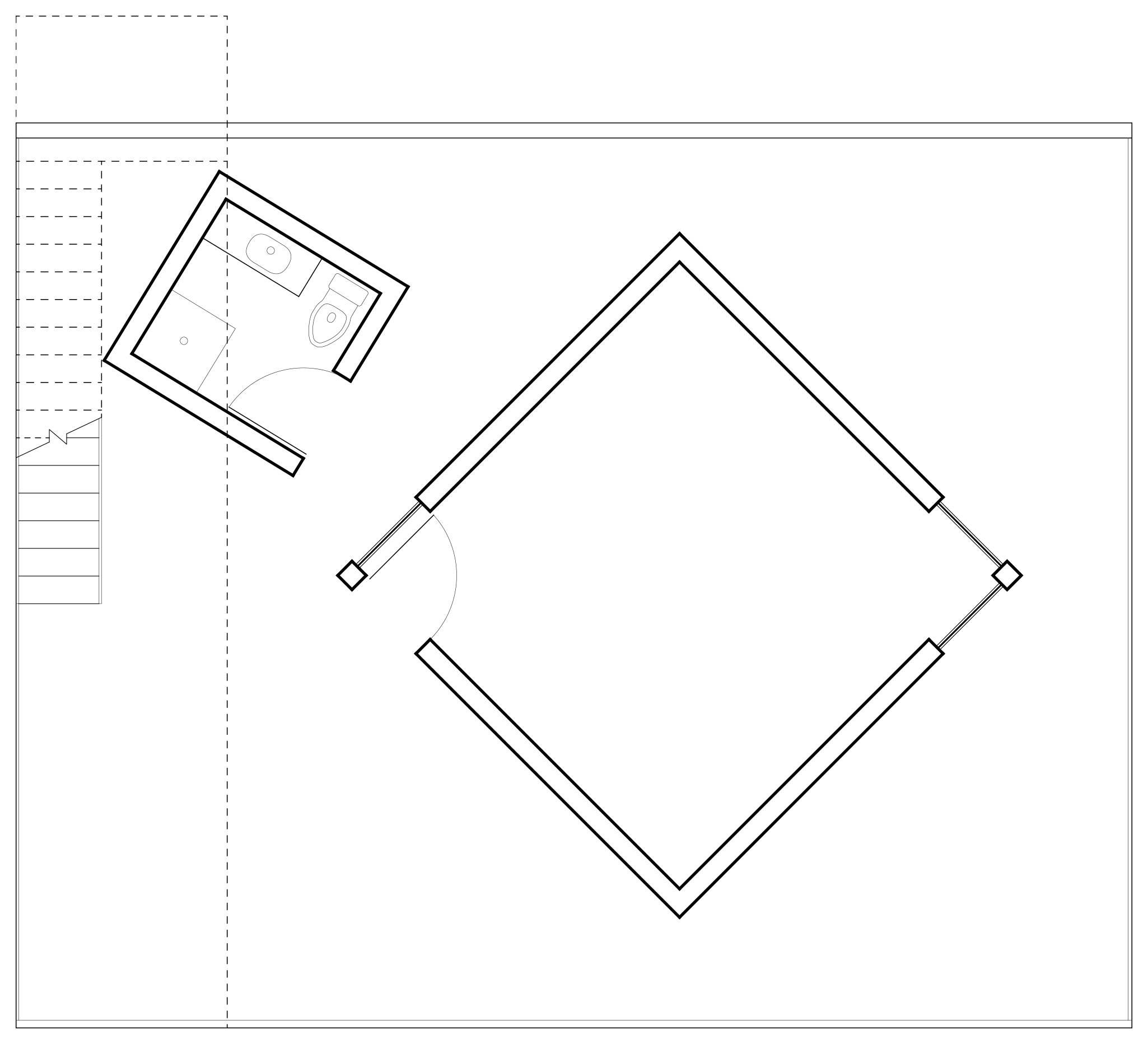

In contrast, the middle level shows a depicted shape operating as a distinct pictorial entity, exerting pressure on the edge that contains it.

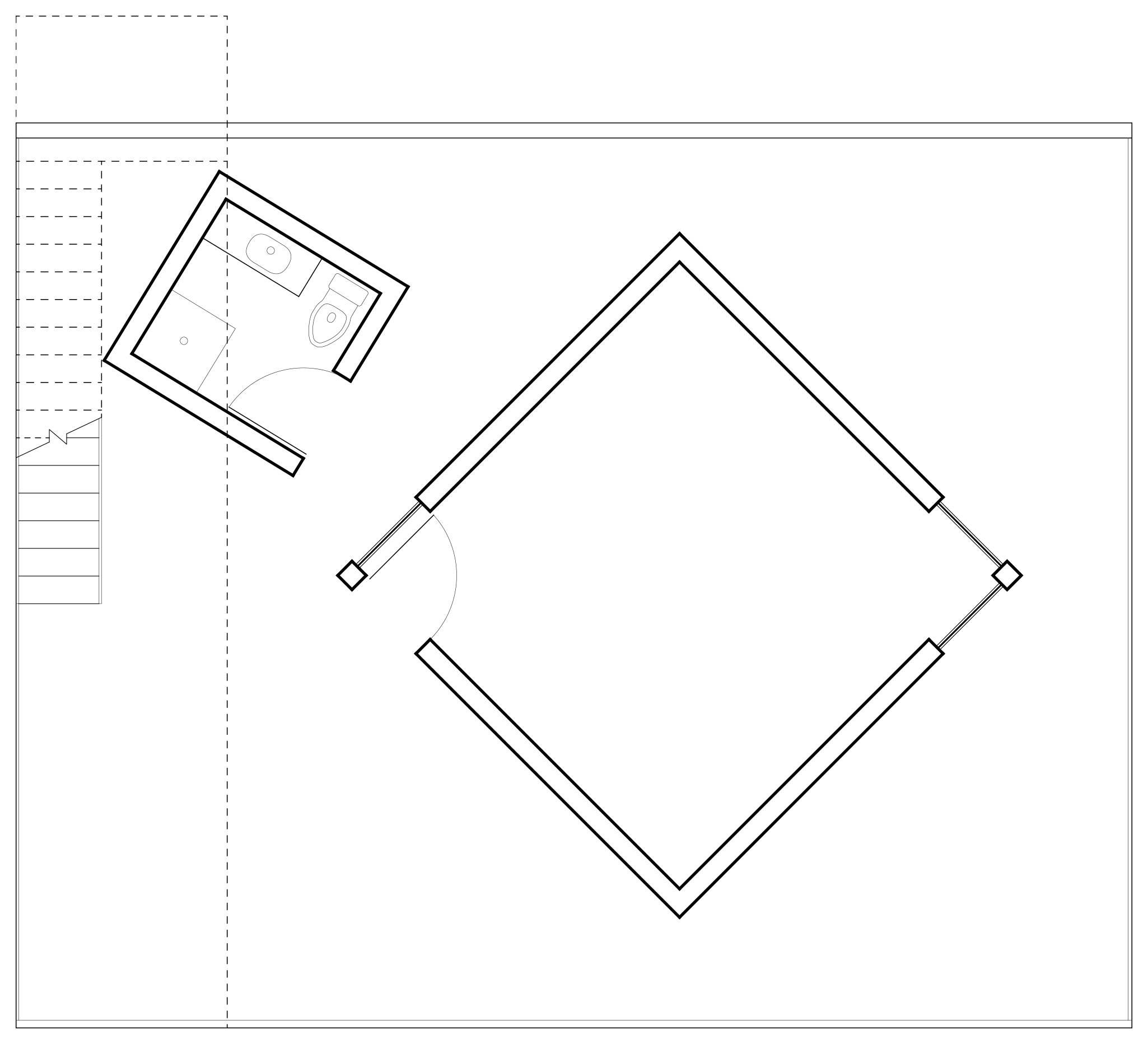

The third and lowest level of the plan has two forms which play against one another without a frame to mediate a relationship, similar to Malevich’s painting. However, in becoming architecture, these two figures show an important difference between pictorial and three-dimensional space: architecture lacks a representational plane. The figures here, free of any frame, do not oscillate between literal and depicted states. Equal in potency, they play out their tensions across inhabitable, three-dimensional space, divorced from their own re-presentation. This is an architectural condition for which there is no analog in painting.

So, if painting oscillates between depiction and physicality, architecture oscillates between figuration and occupation, between form and use. As noted previously, this characteristic of architecture results in two modes of perception: concentrated observation, which occurs when we read form, and habitual use, which occurs when we inhabit form. Walter Benjamin would have us weigh these two forms of perception equally. He argues that habitual use, or perception in a state of distraction, allows for a new kind of perception that is just as canonical as concentrated observation (the mode traditionally aspired to by art), for once we perceive in a state of distraction, perception has become habitual, testing “the possibility of new tasks of apperception.”(3). Habit, then, begets perception, but it also begets form.

In our house, this oscillation is embodied in the form: our L-shaped bands and our diamond figure—the driving forms of our spatial logic—consist of domestic infrastructure. On the upper level, the outer edge, the geometric headspring of the spatial organization, comprises the kitchen and bathroom. On the lower level, the center diamond, our ‘depicted shape,’ not only houses laundry and bathrooms, but was born of the necessity to separate space in order to create private bedrooms. These forms are an infrastructural poché designed for the domestic laborer. They provide work surfaces, house machines, and orchestrate the maintenance and cleansing of the body, the reproduction of life. This is not form for the sake of form. This is not a pattern of use overlaid onto an aesthetic goal. Rather, form and use are one and the same: coextensive. Just as the aesthetic plane of a painting, through the depiction of a grid, becomes one with its own physical surface, so the tension between literal and depicted shape, through the architecturalization of drawn figure, becomes one with the form of habitual use. Our two modes of perception—concentrated and habitual—are simply two ways to see the same form.

This house exists in tension—tension with the history of architecture and the critique of painting, tension between drawings and construction, program and domesticity, form and use. And yet, the tension is not resolved. Rather, the tension is brought to a perfect pitch, where opposing forces are both equal and opposite. The optically-perceived form—the heavy diamond in the center of the space, the rigidity of a rigorous banded logic—exerts upon the habitual a pressure to be made known. And so form coerces a potential for habits to be re-examined. There is something to be said about the value of the struggle between other-worldliness and the reality of the physiopolitical world. But the precise implication on domesticity is yet unknown and it interests us to present it as such. Yet although unknown, an implication is undoubtedly there, as we have taken the hand of form, infringing upon existing patterns of use, to nudge us out of distraction and provide passage between opposite modes of perception. One need not forecast future uses of space. Instead, use, program, habit—automatically placed under the auspices of architecture—are re-thought, re-invented from the rigor of form.

(1) Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985), 18.

(2) Michael Fried, Art & Objecthood (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1988), 77-83.

(3) Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008), 39-41.

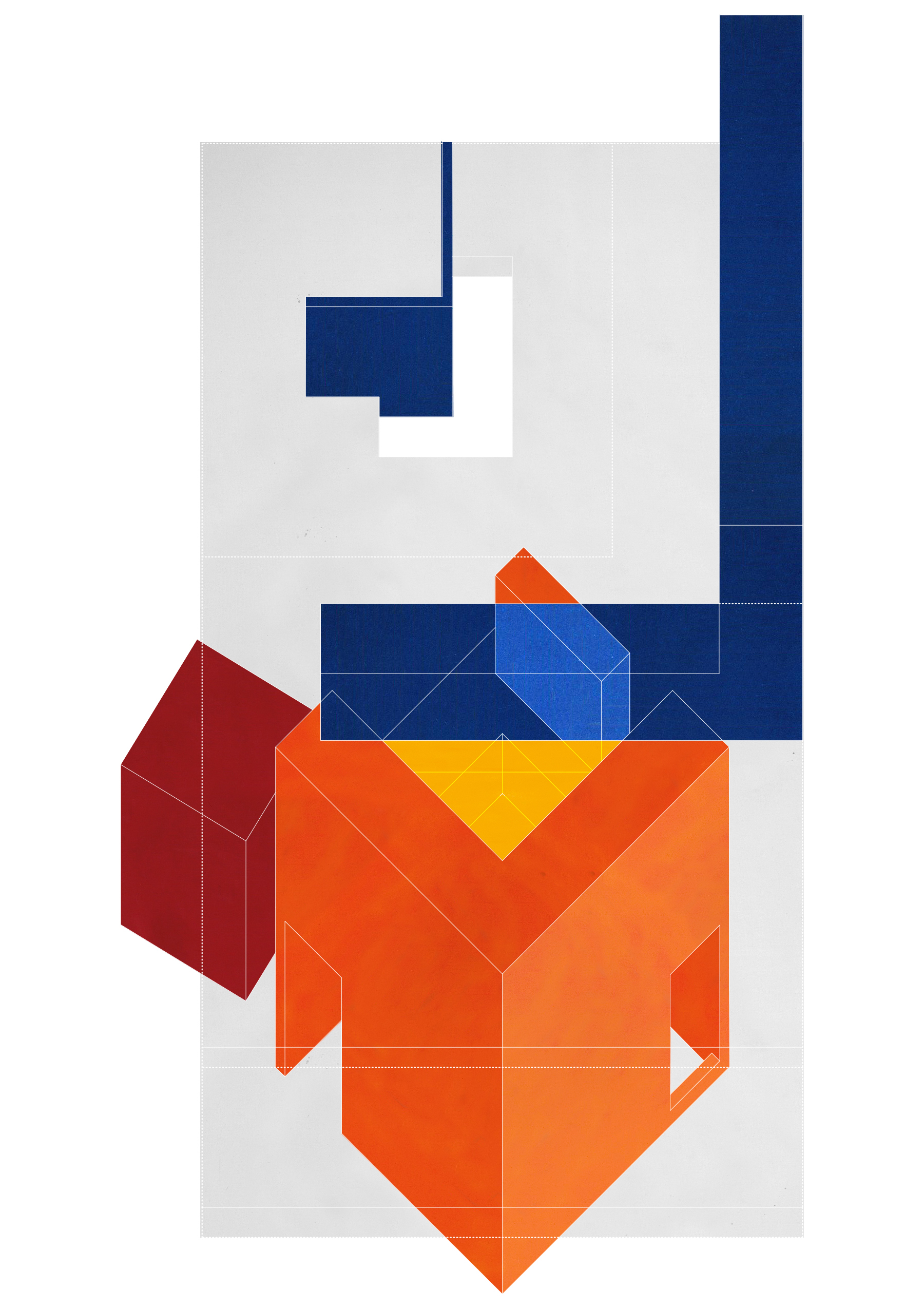

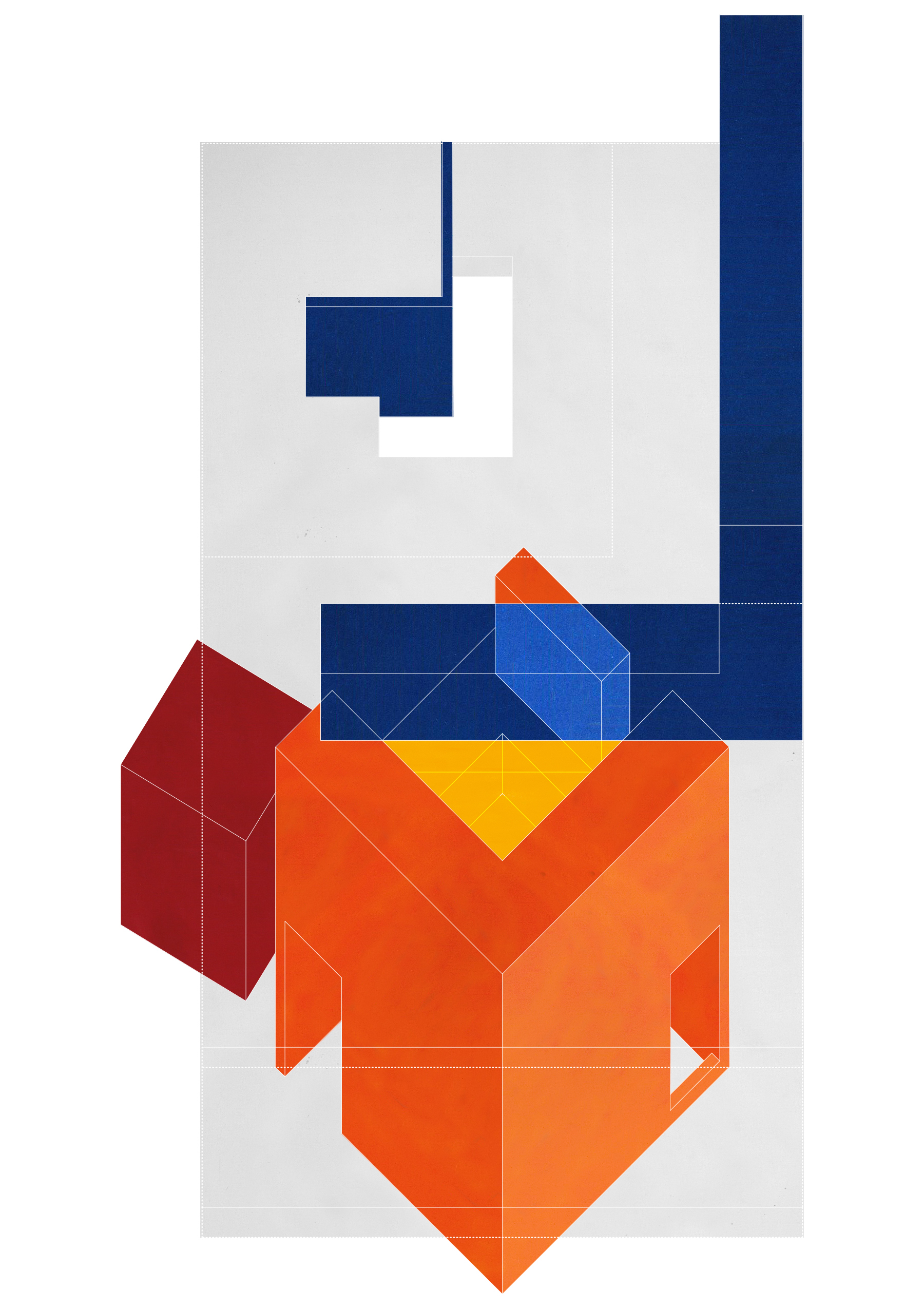

House Painting 01

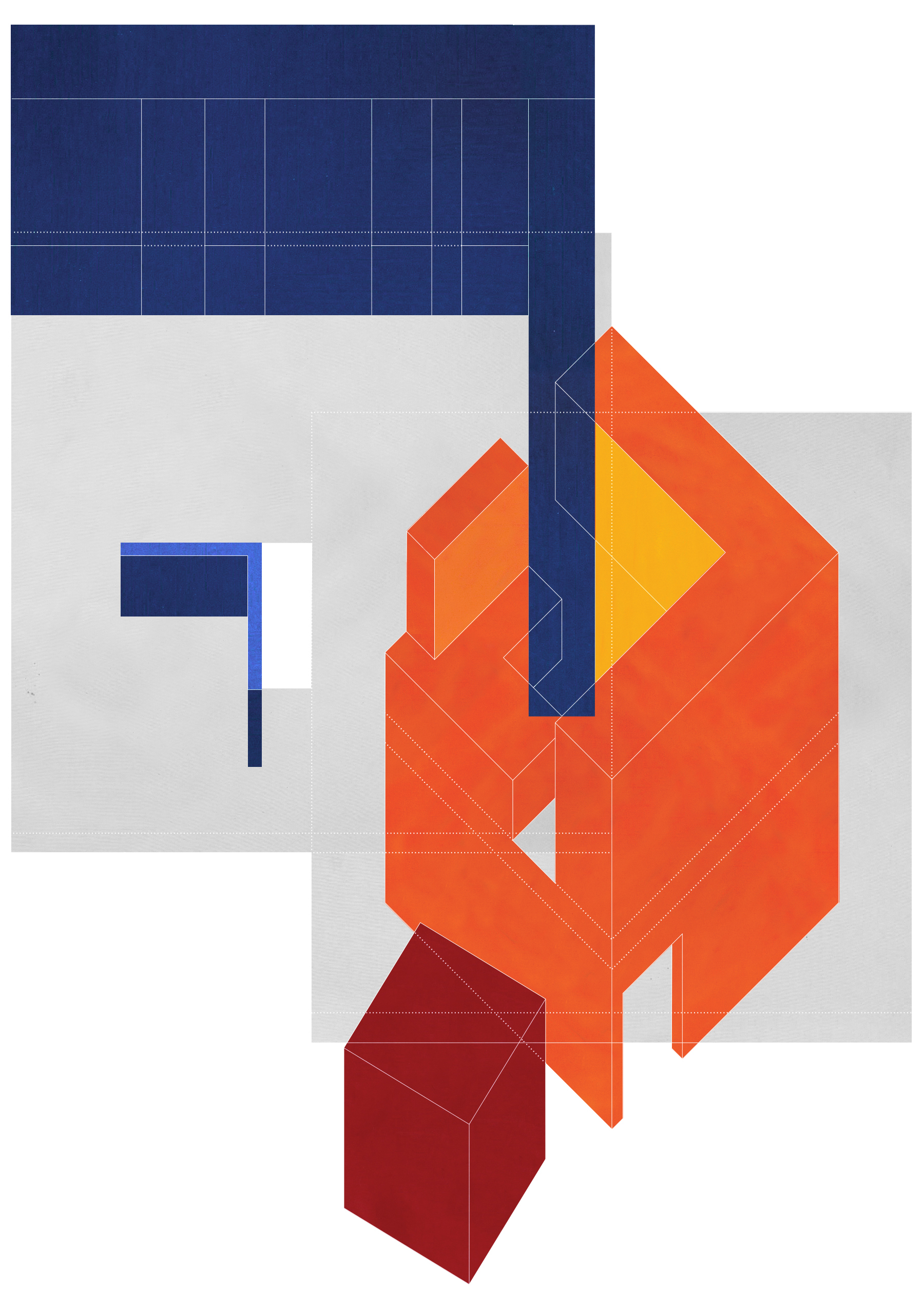

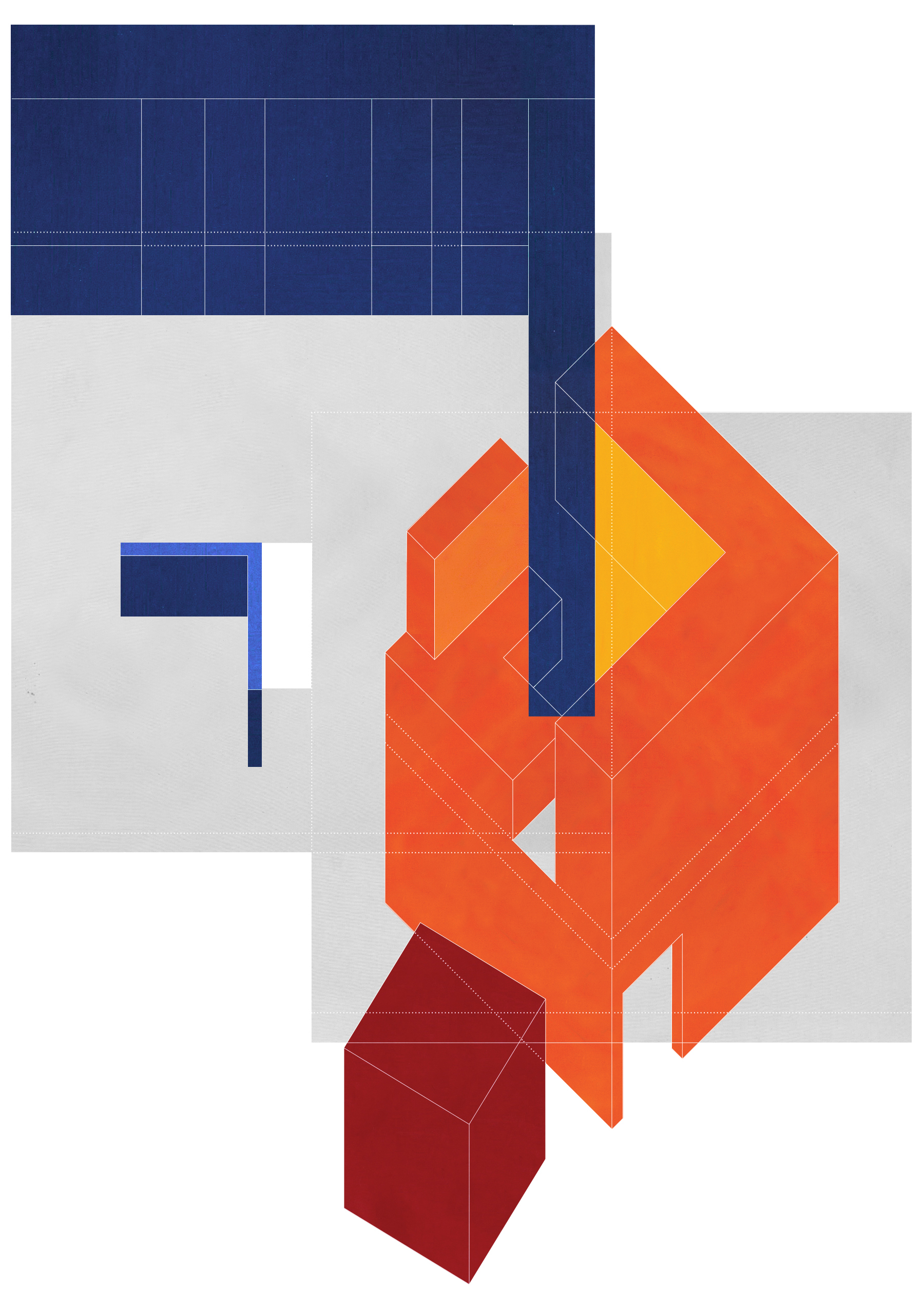

House Painting 02

An initial reading of the plan shows the architecture exploiting the tension between literal and depicted shapes. If the literal shape in painting is the canvas and if the canvas is the field of action, then in architecture our literal shape is the outline of the floor plate, across or against which depicted shapes are laid out, either following or fighting the edge. Here, on the ground which is our canvas, both space and human activity are organized. In our upper plan, the formal logic is governed, as in Stella, by the literal shape, whereby L-shaped bands replicate the edge of the square floor plate.

In contrast, the middle level shows a depicted shape operating as a distinct pictorial entity, exerting pressure on the edge that contains it.

The third and lowest level of the plan has two forms which play against one another without a frame to mediate a relationship, similar to Malevich’s painting. However, in becoming architecture, these two figures show an important difference between pictorial and three-dimensional space: architecture lacks a representational plane. The figures here, free of any frame, do not oscillate between literal and depicted states. Equal in potency, they play out their tensions across inhabitable, three-dimensional space, divorced from their own re-presentation. This is an architectural condition for which there is no analog in painting.

So, if painting oscillates between depiction and physicality, architecture oscillates between figuration and occupation, between form and use. As noted previously, this characteristic of architecture results in two modes of perception: concentrated observation, which occurs when we read form, and habitual use, which occurs when we inhabit form. Walter Benjamin would have us weigh these two forms of perception equally. He argues that habitual use, or perception in a state of distraction, allows for a new kind of perception that is just as canonical as concentrated observation (the mode traditionally aspired to by art), for once we perceive in a state of distraction, perception has become habitual, testing “the possibility of new tasks of apperception.”(3). Habit, then, begets perception, but it also begets form.

In our house, this oscillation is embodied in the form: our L-shaped bands and our diamond figure—the driving forms of our spatial logic—consist of domestic infrastructure. On the upper level, the outer edge, the geometric headspring of the spatial organization, comprises the kitchen and bathroom. On the lower level, the center diamond, our ‘depicted shape,’ not only houses laundry and bathrooms, but was born of the necessity to separate space in order to create private bedrooms. These forms are an infrastructural poché designed for the domestic laborer. They provide work surfaces, house machines, and orchestrate the maintenance and cleansing of the body, the reproduction of life. This is not form for the sake of form. This is not a pattern of use overlaid onto an aesthetic goal. Rather, form and use are one and the same: coextensive. Just as the aesthetic plane of a painting, through the depiction of a grid, becomes one with its own physical surface, so the tension between literal and depicted shape, through the architecturalization of drawn figure, becomes one with the form of habitual use. Our two modes of perception—concentrated and habitual—are simply two ways to see the same form.

This house exists in tension—tension with the history of architecture and the critique of painting, tension between drawings and construction, program and domesticity, form and use. And yet, the tension is not resolved. Rather, the tension is brought to a perfect pitch, where opposing forces are both equal and opposite. The optically-perceived form—the heavy diamond in the center of the space, the rigidity of a rigorous banded logic—exerts upon the habitual a pressure to be made known. And so form coerces a potential for habits to be re-examined. There is something to be said about the value of the struggle between other-worldliness and the reality of the physiopolitical world. But the precise implication on domesticity is yet unknown and it interests us to present it as such. Yet although unknown, an implication is undoubtedly there, as we have taken the hand of form, infringing upon existing patterns of use, to nudge us out of distraction and provide passage between opposite modes of perception. One need not forecast future uses of space. Instead, use, program, habit—automatically placed under the auspices of architecture—are re-thought, re-invented from the rigor of form.

(1) Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985), 18.

(2) Michael Fried, Art & Objecthood (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1988), 77-83.

(3) Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008), 39-41.

House Painting 01

House Painting 02