SUB—POSITION

by Stanley Cho

PART I

An Architecture of Ephemerality

In his L'ARCHITECTURE CONSIDÉRÉE SOUS LE RAPPORT DE L'ART, DES MOEURS ET DE LA LÉGISLATION (Plate 5), Claude Nicholas Ledoux comes upon a “humble édifice,” an Ornamental Barn which the author architect begins to describe, both the building and its builder, an artisan from Dôle.

Ledoux’s description betrays an enchantment of place that is obscured by layers of atmosphere, like a landscape by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. There is a north breeze, a summer sun, suspended clouds, piquant light, accumulated tints of color and shadows cast. “Further off, the eyes rested on golden fields and lost themselves in the accumulated tints of the atmosphere.”(1)

(a)

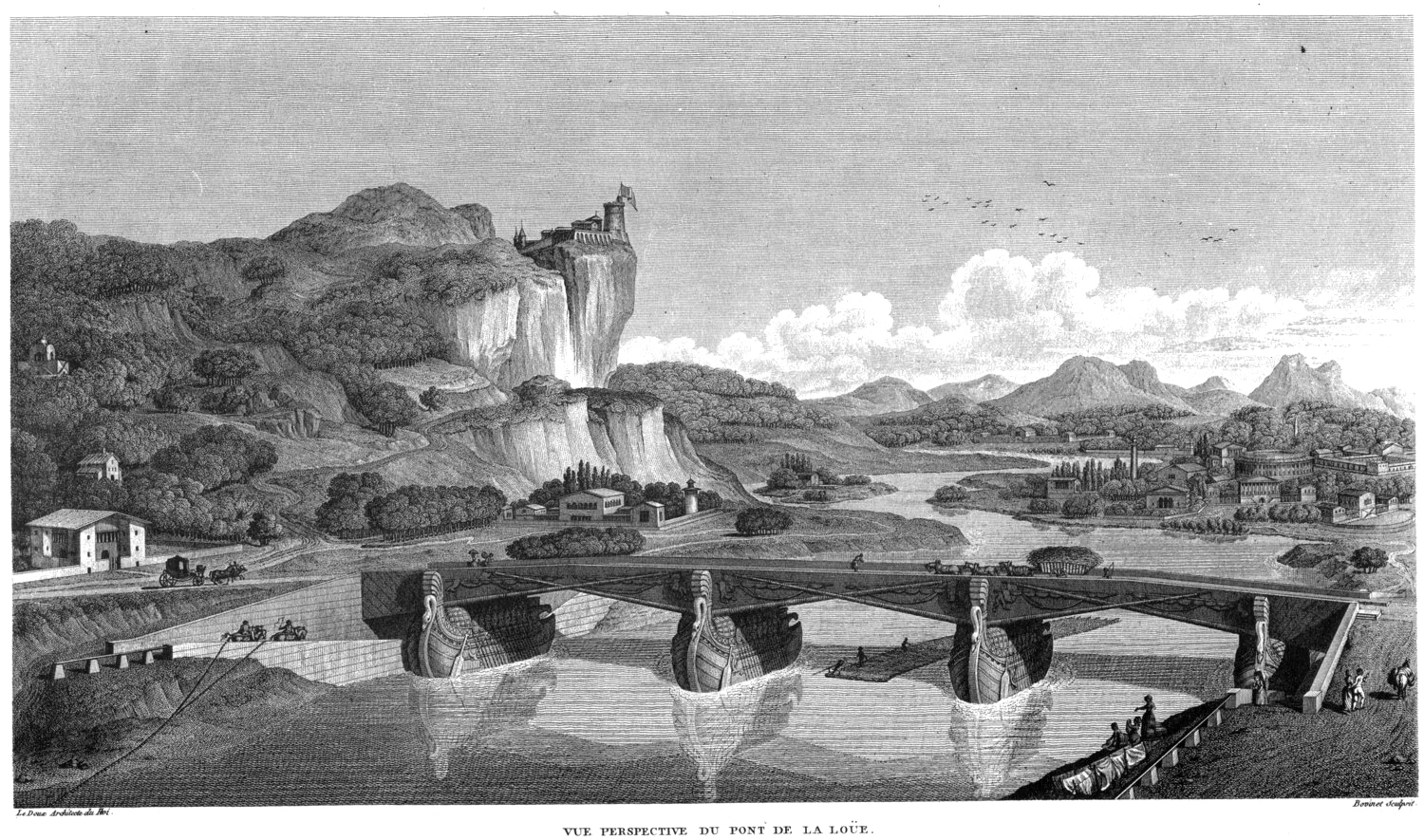

From the slopes and hillock to the texture of leaves, the range of the natural landscape does not escape Ledoux’s judgment of the site. The “demanding terrain” is one that begets a sensual description of nature that goes beyond the visual. The verdure is described with a sensitive attention to detail, textures that are evocative of a sense of touch. The air, perfumed and pure, triggers the sense of smell. Ledoux’s observation of nature exists in the fleeting ephemerality of the senses. The senses comprehend the constant metamorphosis of nature—the morning dew, the burning summer sun with its piquant light, the protective dark shadows, and clouds pierced by mountains. Ledoux’s sense of nature provides a “sweet and delicious” feeling like the taste or smell that lasts for but a moment and cannot be distinguished without its innate impermanence. Thus, the ephemerality of nature is substantial yet elusive in Ledoux’s determination of the site’s boundaries. Especially apropos is his description of the Loue River as foaming with rage, with rocks thrown about haphazardly, hostile toward any obstacle to its constant and spontaneous flow.(2) It is a vignette rendering the animation of nature that captures the power and ephemerality of the scene set before him. Ledoux’s subjective understanding of nature is romantic. He personifies it from his own point of view. However, with Ledoux and in particular in this project of the Ornamental Barn there is a sense of enlightenment and idealism by which the study of nature—or the engagement with nature—would supersede a preconception of living, and undermine the indulgences of hoarded wealth. Nature is the universality of his text. It is the thing which all people understand—rich and poor, educated and rural. Ledoux explains, “Its slopes were in place, and softly extended, flowering trees lined the road, the spaces in between presenting scenes were adorned with useful produce of every kind... I saw abundant vegetables, covered with the morning dew; orchards, protecting the cultivated fields with their accidental shadows; the air was pure and perfumed with every exhalation that could carry to the smell a sweet and delicious feeling.”(3) Sensuality is in the context of fecundity, of “cultivation.” In the eyes of Ledoux there is a perception of nature outside of subjectivity, one that indicates the abundance from which a collective humanity, a “humble” people, gleans its quotidian necessities. At the heart of Ledoux’s observations is the rationality of Jean Jacques Rousseau’s critique of social and political economy where the common necessities of life should be protected and agreed upon through law and social esteem, while the superfluities of wealth need be cautiously kept in balance for the sake of a general good and salubrity of the state. Too often the individual inclination and the general will are incongruous, one benefiting at the expense of the other. Rousseau emphasizes the virtue and integrity of the human heart that are taught since birth, reflected in the principles that for Ledoux shape the physiognomy of the human environment. It is a political and social condition that is readily attainable though rational means. “A mass of people have never been made into a nation of philosophers,” writes Rousseau, “but it is not impossible to make a people happy.”(4)

Humanity

“Everywhere one recognizes the happiness that one obtains from the active life,” writes Ledoux, “Philosophers of the day! Men of the world! Those whose troubles follow behind when you run after pleasures, come here to learn a lesson.”(5) Ledoux recognizes “the humble people who fear to let their existence be perceived.” The artisan from Dôle is one of these who, Ledoux explains, is able to “taste with pleasure a merited eulogy” since “the measure of his means is the good opinion of himself.”(6) In the context of the individual’s modesty, there is the possibility of having a “good opinion” of oneself. “Come here,” to a situation of modest means, “to learn a lesson from an individual who has gathered around him everything which is necessary.” Driven by necessity and sustained by the affluent yield of nature—his fuel for production are the products that are gleaned from his surroundings. The artisan from Dôle does not possess great wealth, yet his revenues are above his expenses.(7) Ledoux’s emphasis is not on the size of revenue, but on the modicum of expenses that stems from the humility of the Artisan’s situation. The common use of the word economy, according to Rousseau, is the prudent management of what one has rather than finding ways of obtaining what one has not.(8) The individual of Dôle utilizes the form and products of nature. It is important to learn from Ledoux’s observation that the individual of Dôle enjoys such products, which are the consequence of nature’s ephemerality. A patriotism (a form of happiness) that Rousseau describes proceeds from such an enjoyment where one participates in the cycle of cultivation and harvest. Primarily, this is a situation where the individual is active, where his productivity makes him, like nature, an animated being. Therefore, humanity too is ephemeral. He is animated not by ambition or fear, but by the vibrancy that economy provides. Ledoux observes the surroundings of the Ornamental Barn through such a lens and sees an animation of nature that is in constant production—from mist to river to humanity—that refuses to be restrained because it knows what is necessary.

“I look upon any poor man,” says Rousseau, “as totally undone, if he has the misfortune to have an honest heart, a fine daughter, and a powerful neighbor.”(9) The carefree life surrounding the Ornamental Barn is contrasted with a magnificent château nearby which “conceals troubles spawned by the embarrassment of great possessions.”(10) Motivated by fear, the rich build high walls for enclosure and do not allow themselves to be linked to the neighboring landscape. In describing the château Ledoux sounds a bit like King Solomon in his Ecclesiastical poems where all art and possession are futile; he criticizes the indulgences of the built world, and he asks rhetorically: “What good is accomplished? Only to leave future generations a land changed in its face.”(11) Rousseau will moreover say that efforts of art and talent are not even necessary in order to manage a healthy society.(12) The physiognomy of the nature of humanity, whether it is the barn or the château, is nevertheless reflected in its environment. Ledoux’s utterance is not simply an admonition of the pointless endeavors of art without purpose. But, it is to caution that “the outrages of art, (its) lying proportions” impede nature, obstruct its movement, its growth, and its fecundity. In other words, the outrages of art, embodied by the château and its support systems hamper nature’s inherent ephemerality.

“If amour-propre mingles with all the passions, if it directs them,” writes Ledoux, “it is the vehicle of the interior sentiment that betrays presumption.”(13) Amour-propre is a disposition, defined by Rousseau, whereby esteem exists only in the presence of society. Rousseau would ask, “How can patriotism germinate in the midst of so many other passions which smother it?” In his Discourse on Political Economy, such esteem in the presence of society would be the very reason for constructing such a château with its embellishments. He writes, “They must know but little of mankind those who imagine that after they have been once seduced by luxury, they can ever renounce it: they would a hundred times sooner renounce common necessities, and had much rather die of hunger than of shame.”(14) According to the artisan of Dôle, the desire for enclosure and seclusion, though ironically constructed by the influence of society, runs contrary to nature; and self-esteem cannot be won with a self-sufficiency at odds with the tendencies of nature. The owner of the château would likely object with the notion that if his rank were taken into account, what may be superfluous to a man of inferior station is necessary for him. “But this is false,” Rousseau might retort, “for a grandee has two legs just like a cow-herd, and, like him again, but one belly.”(15) The artisan from Dôle hence describes the situation of the château as somewhat of a monstrosity: “You see, he said to me, that magnificent château that conceals the troubles spawned by the embarrassment of great possessions? Those high walls that circumscribe numerous flocks, those young shoots withered by murderous teeth, those precious trees lost to the present race; do you see those proud pines that electrify the clouds, those vast branches that paralyze the efforts of a generous earth, those trunks stripped bare whose split bark announces their destruction? Do you see those trees whose abandoned tops launch majestically into the air? Their ruin is near; it is inevitable.”(16)

Architecture

“Abundance squeezing an impotent breast… (with) limitless possessions that are confided to the care of covetous agents because of the impossibility of overseeing them oneself, (they) are bounded by that exclusive fear that concentrates false enjoyment, and does not allow them to be linked to the neighboring landscape.”(17) The architecture of the château is self-contained. The architecture is not linked to the site that Ledoux is surveying.

(b)

It is also a container presumably for all sorts of ephemera. “The paving presented a sample of every marble, of all known enamels; it is strewn with Etruscan vases, Japanese plates; magnificent bronzes support the chafing dishes where the extracts of vanilla and cinnamon burn.” The architecture of the château is a container for possessions, rather—an encasement for a kind of permanent ephemera. Like “an impotent breast,” these are ephemera that do not produce anything.(18) Even the cinnamon and vanilla seem to coax the inhabitant into a stupor of indolence and stagnation. Thus, ephemerality is no longer animated in the same way that it is for the Ornamental Barn. It is a movement associated with social mobility. The movement of the château owner is not motivated by necessity, but is rather a result of the continual shifting of rank and fortune among the citizens that Rousseau finds to be fatal to morality. In the context of the superfluity of he rich, the idea of permanence and ephemera is a contradiction that can solely be reconciled in ruin. Jean le Rond D’Alembert regarding architecture in the Encyclopédie would understand such a château as “only the embellished mask of one of our greatest needs.”(19) Rousseau’s Discourse on Political Economy, which was also included in D’Alembert’s Encycolpédie, explains that ephemera such as the château and all it contains are the very things which should be taxed. The frivolous and lucrative arts should be taxed “to prevent the continual increase of inequality of fortune and the multiplication of idle persons in our cities…heavy taxes should be laid on servants in livery, on equipages, rich furniture, fine clothes, on spacious courts and gardens, (while) he who possesses only the common necessities of life should pay nothing at all.”(20) But moreover, it seems for Ledoux that the château instills something insidious within the physiognomy of the land. It is that which frustrates the nature of nature. Therefore it is not simply architecture “perfected by luxury”—a refined variant of the barn where function begins to be understood as separate from the form.(21) But indeed the form is functioning in a way to further establish a controlled confinement and mores around the amour-propre which Ledoux criticizes in his observations as a concentration of false enjoyment that stamps out human caprice.

Contrary to the architecture of the Château, Ledoux admires the masterful architecture of the artisan from Dôle and his intelligent use of the found site: It is a site “favoured by nature” which “owes nothing to art.” The artisan explains, “Not being limited by any stone enclosure, I have joined myself to the surrounding sites by means of a ditch and preserving hedge.”(22) The architecture here is not self sufficient. It is “hedged in.” It is not an architecture concerning volume or the symbol (mask), but one concerning necessity and the temporary. The artisan from Dôle does not see nature as an amorphous other. It is an ordered means to an end—a technology for meeting human needs and an essential tool of productivity. Not being wealthy enough, the artisan from Dôle who Ledoux later refers to as “my little economist,” combines both the details of a farm and the comforts of dwelling in a small building. It has the imprint of his economic faculties. “Everything” he says “is motivated by necessity.” The architecture of the ornamental barn is not simply the square mass with pediment held by two pillars spaced at two diameters.(23) It is rather defined by the objects of necessity it houses. Within and without its boundaries are the ephemera of quotidian objects.

Ornament

One can only infer then that the ornament of the Ornamental Barn does not exist on the face of the building, especially in a Humanist sense of Virtruvian orders or in a French classical sense of Character and Decoration, but it manifests in the redolent nature of the whole ephemeral situation—the nature that situates and imposes and, in fact, overwhelms the building together with the fecundity of life without a trace of luxuriant pleasures: Carriages, carts, washing places, fountains for fire prevention, agricultural storehouses, hanging fleeces, clay pots filled with milk and fruit, and even the pleasant slopes which display “a rustic luxury.”(24) Ephemeron as ornament produces the enjoyment of the products of cultivation and the enjoyment of the land that the eyes have the capacity to perceive.

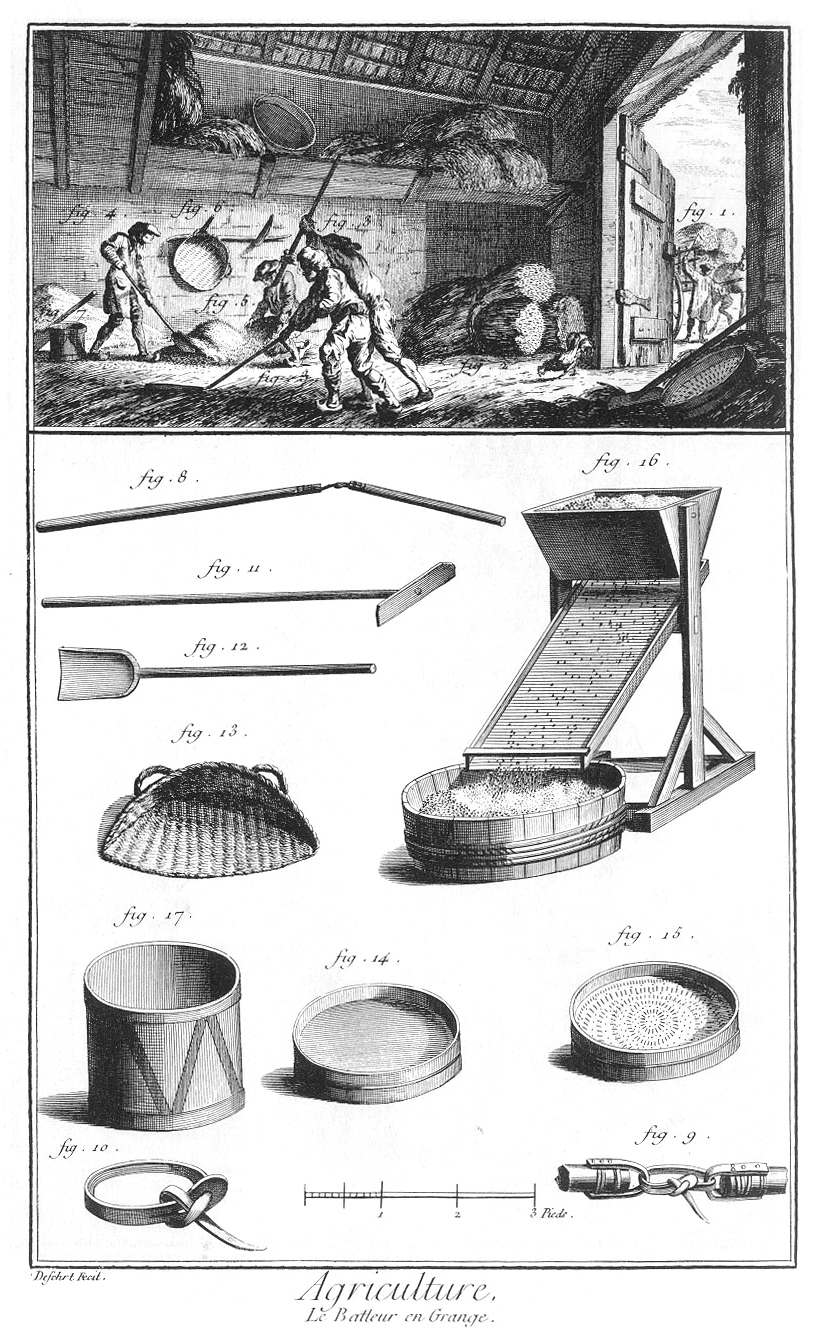

The Encyclopédie

Anthony Vidler concludes in his essay “Architecture and the Enlightenment” that Ledoux had the idea that “the foundation of a city would be much like the construction of the Encyclopédie.(25) Perhaps this was Ledoux’s attraction to the barn. It was an architecture of necessity, encyclopedia-like in its natural display of essentials, like a catalogue of necessary ephemera. In the Encyclopédie, quotidian objects are neatly laid out on the pages. For example, one such page shows threshers in a barn and their tools: Un fléau à grain, rabot, a shovel, instruments for winnowing grain, sieves, and measuring tools.

(c)

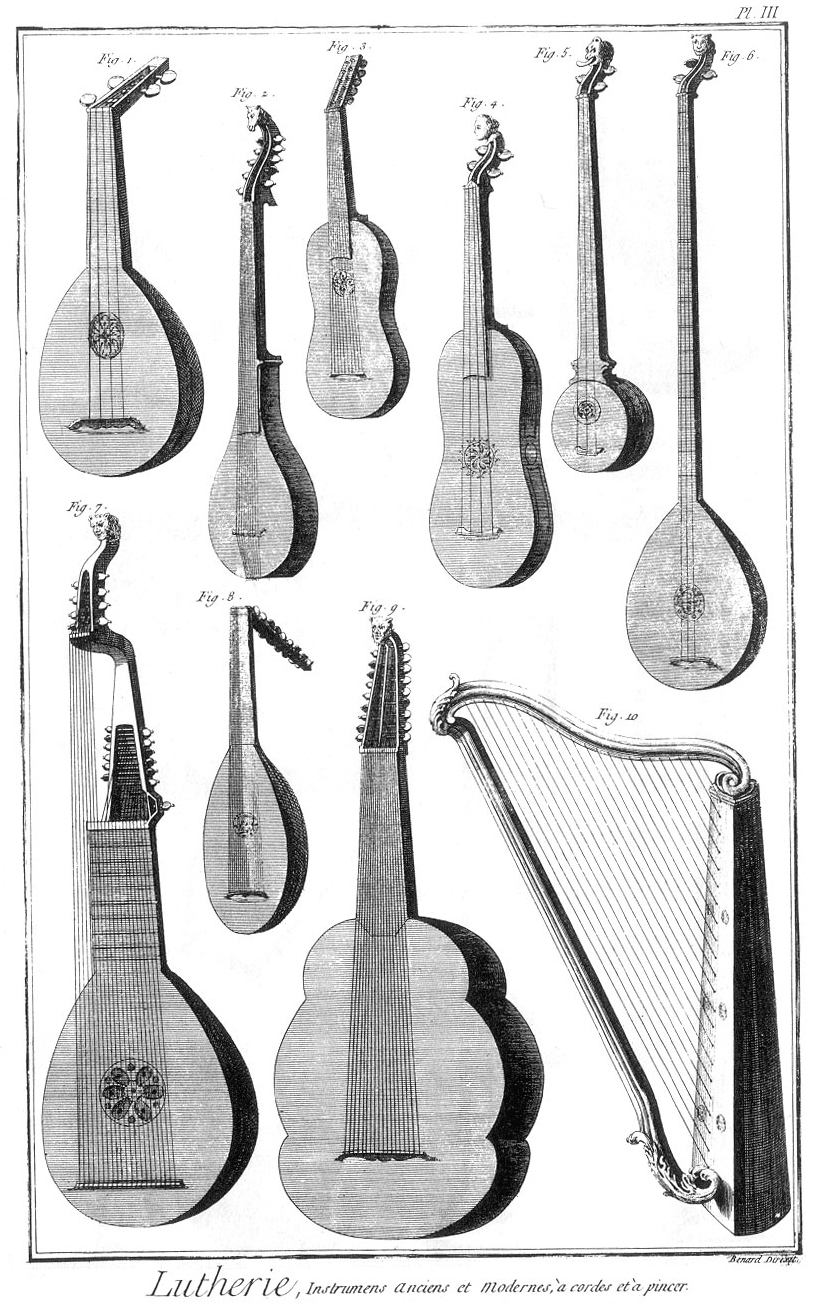

Another, on the topic of ancient and modern musical instruments, displays various types of string and plucked guitars.

(d)

The ephemera of life take center stage. This is the content of the Encyclopédie and thus the means to possessing knowledge, thereby enlightenment—perhaps suggesting that knowledge itself is ephemeral: it changes with nature.

The Co-op Zimmer

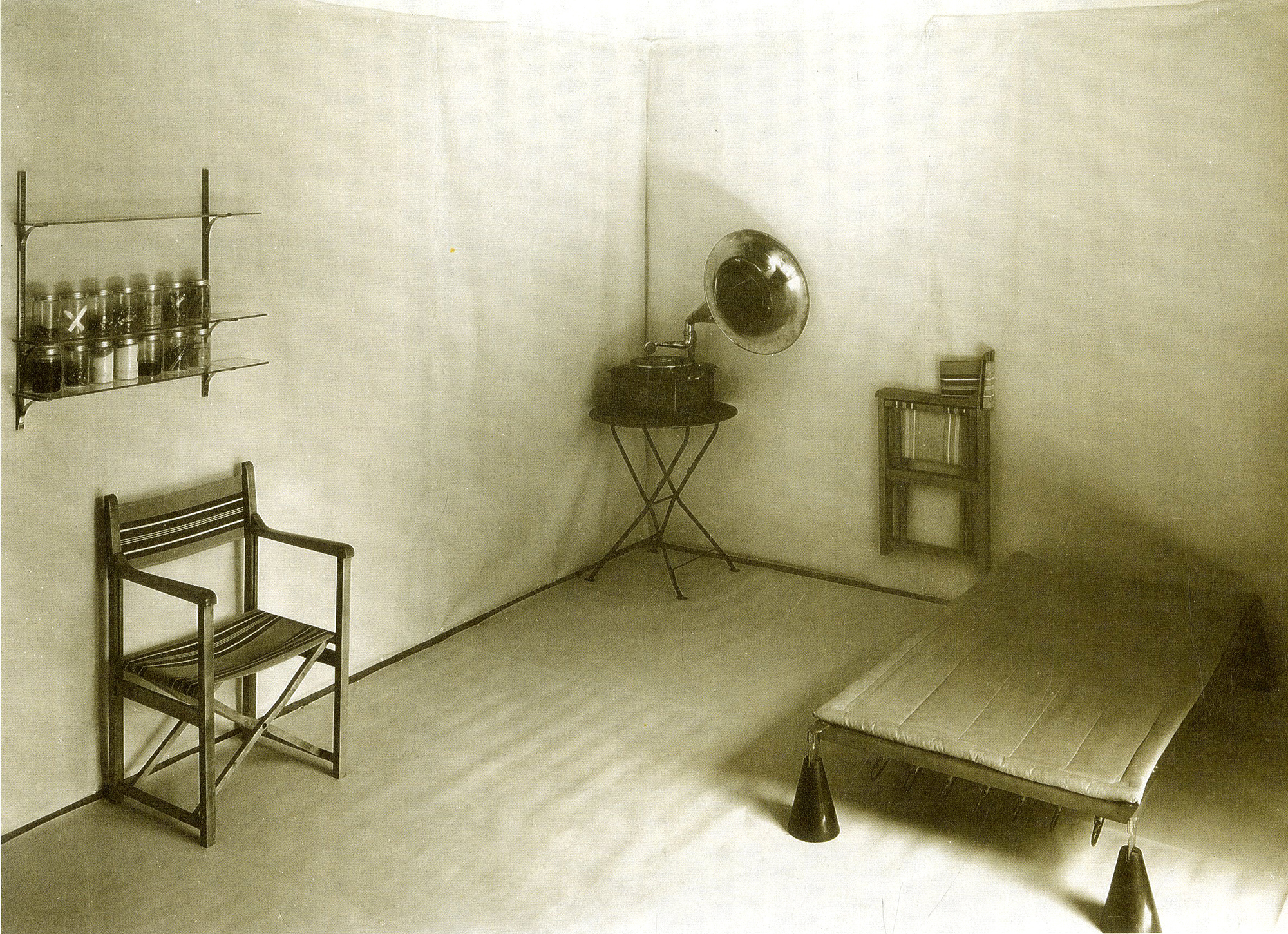

Emil Kaufmann wrote a book entitled Von Ledoux bis Le Corbusier: Ursprung und Entwicklung der autonomen Architektur. He proposes that Ledoux prefigured Modernism with his proto-bourgeoisie architecture of geometric and volumetric abstraction that signified the autonomy of architecture.(26) Conversely, with this project by Ledoux one might instead make the connection to the architecture of Hannes Meyer, another figure who, like Le Corbusier, helps canonize the project of Modernism, but who ventures to absolutely dissolve the autonomy of architecture into a biological process. More specifically, with Meyer, the separation between distribution and decoration need be obliterated if architecture in the industrial age is to have relevance. Autonomy then lies in the expertise and objectivity of architecture in a sea of knowledge and problems. In 1924, Hannes Meyer’s Co-op Zimmer was displayed in an exhibition in Ghent on cooperative design. It was a project for an interior.

(e)

However it should be noted that the Co-op Zimmer is not a built work of architecture. The project is a photograph. It was subsequently published with his article “Die Neue Welt” as an example of the aesthetic of standardization, repetition, mechanized media, advertisement, nomadism, impersonality, and collectivity.(27) The interior is represented by a mock-up of white fabric, a folding chair of canvas and wood, a cot raised on conical feet to allow air to flow underneath, and a gramophone on a collapsible stool; the un-cropped version also shows shelves of food products.(28) The collapsibility of these objects is analogous to the motif of ephemerality in Meyer’s essay. Furniture is reduced to the bare necessities for the inhabitation of an individual. The Co-op Zimmer is an architecture motivated by necessity. The individual inhabitant of the Meyer interior has gathered about him everything that is necessary. The artisan of Dôle can in the age of modernity in the Co-op Zimmer unlock the good opinion of himself in the context of modesty. Possessions as ephemera rather than possessions as property liberate the inhabitant from the amour propre and the “false enjoyment” of the more permanent château. Instead, the room like the Ornamental Barn is a tool for productivity, providing a possibility of solitude and concentration.(29) It reaps from the natures of technology in order to maintain the animation of humanity—its caprices unimpeded by expenses which are above revenues—a way of life beyond property.(30) Meyer deploys mechanization (advanced production) as a latent network of possible new relations of perception and not as a determining fact.(31) These new relations of perception would otherwise be hindered by the paradigm of the château; obstructed by an interior for concealment with its high walls and stone enclosures. Instead the artisan of Dôle in his barn and in Meyer’s Co-op Zimmer enjoys the “products of (his) cultivation and all the lands that sight (and the various other senses employed by Ledoux) can embrace.”(32) Everything in Meyer’s interior is ephemeral. The white fabric and folding furniture suggest the transience of the space. However, not only is the ephemera of the Co-op space the objects in the photo; but the unforeseen objects, the perpetual ephemera of necessities to come and go in the activity of production and leisure suggested by the emptiness of the room.

Gramophone

But the presence of the gramophone is somewhat contradictory to an architecture of necessity. It is the only superfluous object in the room since it does not have a direct anatomical function. Its curvy shape is in contrast with the restrained atmosphere of the space.(33) But the gramophone also acts to signify an element of unproductive time. Michael Hays in his essay “Diagramming the New World…” calls out the reiterative circles of the gramophone. It is these circular forms—the conical bed feet, and especially the circular grooves of the record and horn of the phonograph which give the Co-op interior a sense of “calm and hedonistic enjoyment”(34) as Pier Vittorio Aureli points out in his essay “Less is Enough”. The spices in the jars on the shelf have to do with food and the function of bodily nourishment, but they also pertain to the sense of smell. In the same way, the gramophone indicates the sense of hearing. The Co-op Zimmer is hedonistic and sensual. Aureli further points out in his essay “The Theology of Tabula Rasa” that the superfluous gramophone evokes a sense of ephemeral inhabitation driven not only by necessity but also by choice.(35) It is a deliberate form of life according to the volition of the individual, where the development of one’s property is not considered to be of lasting value. Again, with the presence of the gramophone, permanence is spurned. The very un-architectural reality of sounds emanating from the vinyl is a wonderful temporary reality. It fills the simple space. Is there anything lighter than the lightness of music? It too is architectural ephemera. Like the Purist paintings of Amédée Ozenfant and Le Corbusier, quotidian objects—milk jars, wine, decanters, table, chair—share the space with a guitar. Music, indicated by the gramophone and the guitar, is an inevitable continuation of the day.

(f)

Paintings by Le Corbusier

The paintings of Le Corbusier often depict the objects of the quotidian in a kind of interpenetrating relationship to space. Like in the description of the Ornamental Barn, the objects of use are in the foreground. The objects obstruct the continuity of space and are never encased in a background; they are not meant to be looked at or viewed. There is perpetual interaction. In the château, such objects are on display and have an equivocal purpose. In the architecture of the château, objects are both things and possessions; they have no further link to the quotidian. But the quotidian objects in Still Life (1920) are those which signify the activities which might fill the frame of Le Corbusier’s Maison Dom-ino (1914), one of his first architectural projects. The Maison Dom-ino is filled with ephemera. The Maison Dom-ino is the frame for Still Life. The empty concrete architecture implies the establishment of relationships in flux, an interpenetration of abstracted objects outside of a stable modality of perspective. For the quotidian is not meant to be viewed; nor is the quotidian about viewing architecture. However, the everyday is meant to be lived with all its objects in use, in perpetual interaction. Objects then are understood not as possessions, but as ephemera–dissolved into nature. Even memory is dissolved into superfluity and necessity as it becomes clearly associated with an elusive permanence. Memory is not memorialized nor formalized into architecture—but itself is a framed continuance in the act of living. Fleeting memory, perpetually elusive, is inextricably met with necessity; it demands constant renewal of searching for it in order to capture the reality of it. The abstraction of memory in a quotidian context is the redemption of sentimentality. This is the opposite of “false enjoyment.”

Mechanization as Natural

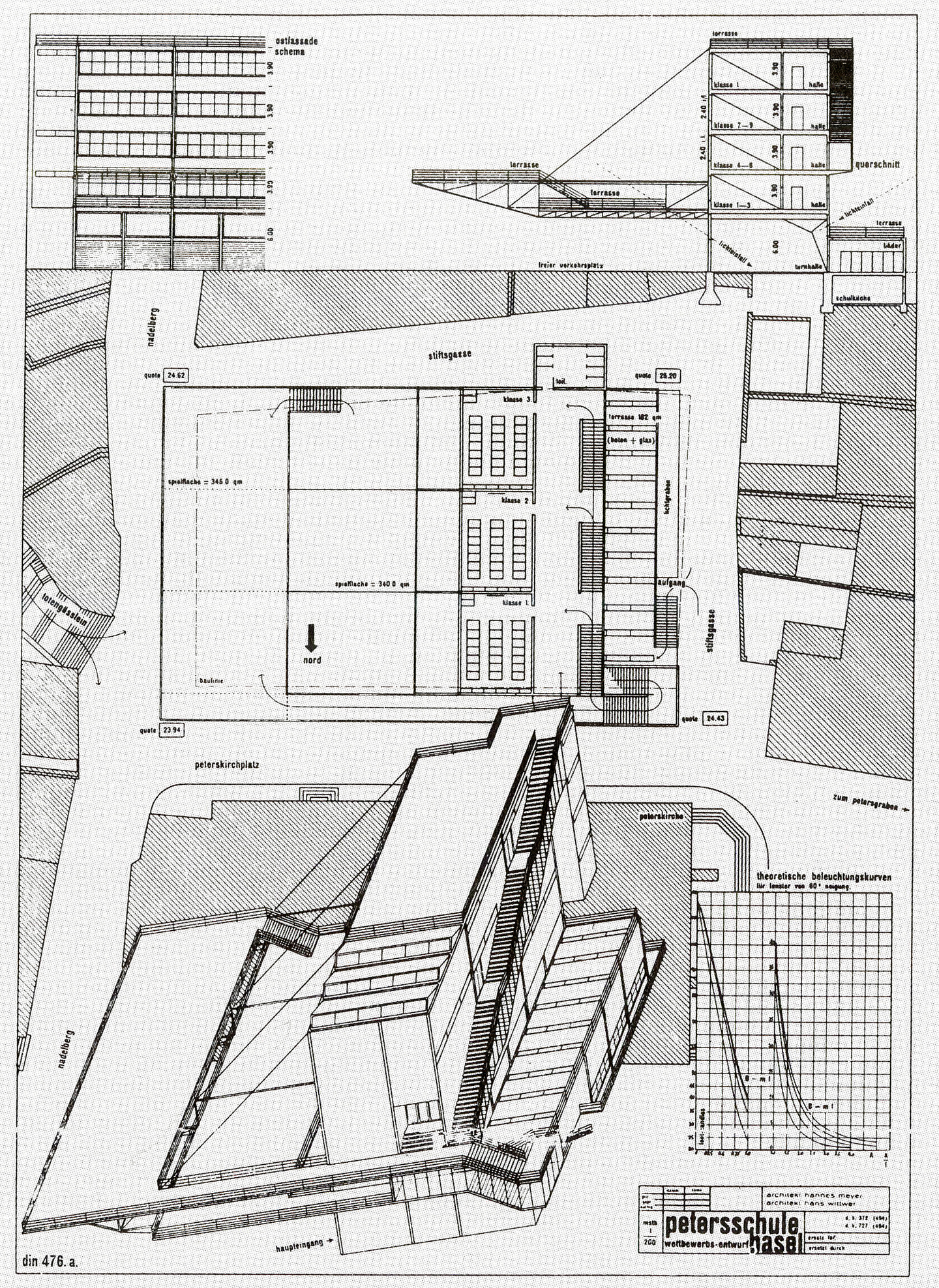

The project of Hannes Meyer, especially in the Co-op Zimmer, combines the frame of building and the objects of ephemeral activity. It is an enlightened Maison Dom-ino, joining with it the subject of Le Corbusier’s Still Life. The contents of D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie come together in Meyer’s architecture of ephemerality. The plate that catalogs barn tools and the one of musical instruments together with the implication of their use are consummated in Meyer’s project. Hays poignantly observes: “it is as if across a graph of advanced technology and media, a membrane has been stretched, a membrane of everyday, domestic use objects that (immediate and familiar as they are) make actual the otherwise purely virtual graph.” This membrane of ephemera inextricably connected with the graph of technology dissolves the established boundaries within various forms of experience and cognition.(36) The Co-op Zimmer and also Meyer’s Petersschule, yield a particular understanding of the science of architecture in a series of mutual reductions and enfoldings.(37) The Petersschule is a design of a school for girls and more explicitly embodies Meyer’s scientization of architecture.

(g)

It is an architectural encyclopedia, a catalogue that projects applied knowledge. Although the Petersschule was equally meant as a didactic tool, like an encyclopedia, the education arrives not from the ever-evolving content of the Encyclopédie, but from the form of the Encyclopédie, its method of arrangement of objects. The ephemera is indifferent or superfluous to space and volumetric form (but vital to Meyer’s understanding of biological processes), but nevertheless, in their organization begin to impose on space and the idea of architecture. The architecture is unfolded into technology and science. Architecture is redeemed not on the basis of art but on the basis of knowledge, as technology and science hence unfolds into nature. For Meyer, technology, science and mechanization are the generosities of earth which should not be blocked by acquisitive notions of architecture. Technology and science are cogent evidences of the victory of man over amorphous nature.(38) The individual of self-esteem in his use of nature does not “paralyze the efforts of the generous earth” but reaps from it his revenue of necessity and enjoyment.

Hierarchies

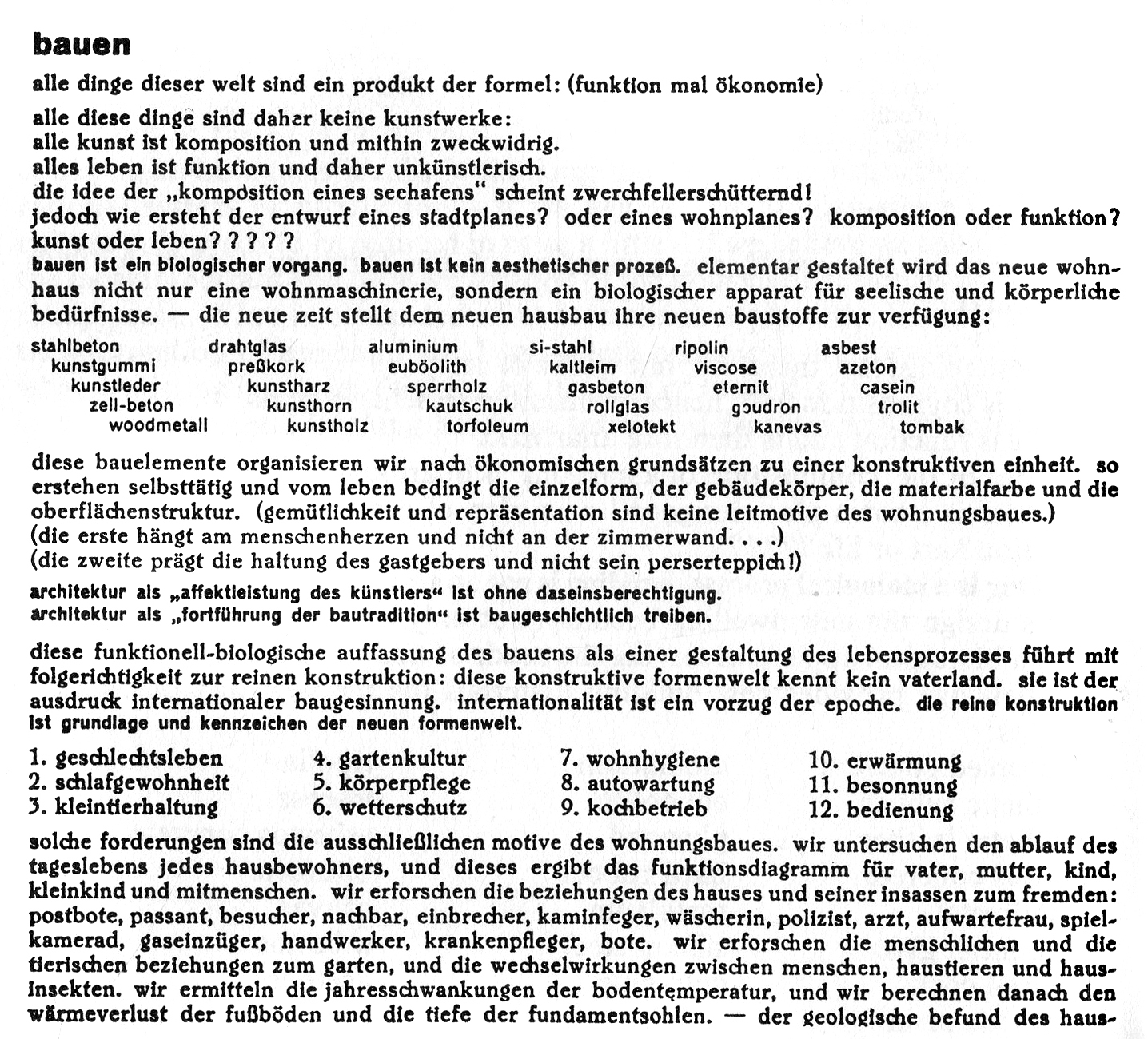

Hays writes that Meyer’s diagram for the present age is “a functional diagram for the kind of mental retooling the human subject must undergo to divest itself of its historically conditioned defects and failures of development and begin its journey toward a classless future.”(39) There is still a fundamental agreement with the politics of Rousseau in the sense that “the most important functions of government is to prevent extreme inequality of fortunes; not by taking away wealth from its possessors, but by depriving all men of the means to accumulate it; not by building hospitals for the poor, but by securing the citizens from becoming poor.”(40) For a classless society is not a utopia in itself, but a result of the utopian effects which are found in nature. A classless existence is a provocation read in the Ornamental Barn, with its observations on the ubiquity of nature and its indifference to class. One can read in Meyer’s projects not only hopes for architecture to unfold into a socialist future but also more simply an underlying attitude sympathetic with the sentiment of the artisan from Dôle. He writes in his manifesto “Building” that “(snugness and prestige are not leitmotifs for dwelling construction)(the first depends on the human heart and not on the walls of a room…)(the second manifests itself in the manner of the host and not by his Persian carpet!)”(41) At the heart of Ledoux is the diagram of Meyer.

The Purist paintings especially the later ones can also be seen as a functional diagram the way they dissolve objects into a relational network. The quotidian objects described above are no longer locked into a binary movement between figure and ground, foreground and background, but are free to move in a less determined way.(42) The paintings are evocative of the un-hierarchical quality of ephemera with their ability to move about uninhibited. The dissolution of perspective is the dissolution of hierarchy.

(h)

“Building” was published in bauhaus, year 2, no.4 in all lowercase lettering. Perhaps this is Meyer’s de-emphasis on the conditioned tendency toward hierarchy.

(i)

It reads slightly different in English, where only the first letter in a sentence and proper nouns should be capitalized. In German grammar, normally the start of a sentence is capitalized, and all nouns are capitalized. His underlying intention than particularly in German is more provocative. The noun, the objects and subjects, are put on equal footing with the verbs and prepositions. The permanence usually associated with the built manifestation of architecture, the capitalized noun, is made equal in importance with the activity of living and more specifically with the act of building inherent in the verb; and furthermore, with the relationships of people, things, and actions signified in the preposition. The project of Meyer is decidedly an architecture with a lowercase “a”.

More Ornament

With the dissolution of compositional hierarchy, Meyer’s Petersschule disenfranchises vision as the dominant category of architecture.(43) In the same way, with its connection to production and necessity the ornament of the Ornamental Barn is an enjoyment beyond the surface. Meyer writes, “Building is a biological process. Building is not an aesthetic process.”(44) Aesthetic, architecture in a visual sense, is determined by “life” or living, through necessity. Meyer confirms, “the colour of material and the surface texture evolve by themselves and are determined by life.”(45) Ornament takes on an other meaning. It is ephemera. It is as effective as the nature of human ephemerality. “The stairs, walkways, and suspended platforms of the Petersschule are standardized or confiscated like so many found elements and affixed or grafted onto the basic unit of the building.”(46) This is the ornament affixed to architecture. Ornament for Meyer is mechanization fused with life and psychology; it is the science of living, which is equated to nature. Hays further writes about the site strategy of the Petersschule: its preeminence of the diagonality so apparent in the perspective and axonometric drawings which block any frontal reading of a humanist building “face.”(47) Meyer deliberately avoids an architecture that might be the embellished mask criticized by D’Alembert.

Von Ledoux bis Meyer

Both Ledoux and Meyer pose questions which radically scrutinize the proclivity of architecture. Whether it is in the form of the poetic or in the abstraction of the diagrammatic, both Ledoux and Meyer proffer answers on how to apply the intangible while taking the form of the ephemeral so that they tend toward a universal cultivation of humanity. From Ledoux to Meyer one can perceive the unfolding of new possibilities, “new types of reality” with ephemera as nature, graph and membrane—indicating the totality of architecture —“the total architectural apparatus” which entails far more than the space and material of a building.(48)

If Meyer’s diagram of the present age is at the heart of Ledoux, then Meyer’s Co-op Zimmer is a design for the fecundity of the Dôle artisan, who is able to possess one’s self esteem. In fact, this artisan from Dôle is in community with Meyer, as one of his aphorisms plainly states, “Building is a communal effort of craftsmen and inventors. Only he who, as a master in the working community of others, masters life itself… is a master builder.”(49) In both Ledoux’s and Meyer’s vision of architecture, the architect is replaced by a new kind of visionary.

(1) Ledoux, Architecture Considered in Relation to Art, Mores, and Legislation, 42.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Rousseau, A Discourse on Political Economy.

(5) Ledoux, 42.

(6) Ibid, 43.

(7) Ibid, 44.

(8) Rousseau, A Discourse on Political Economy.

(9) Ibid.

(10) Ledoux, 43.

(11) Ibid, 44.

(12) Rousseau, A Discourse on Political Economy.

(13) Ledoux, 43.

(14) Rousseau, A Discourse on Political Economy.

(15) Ibid.

(16) Ledoux, 43.

(17) Ibid.

(18) Ibid.

(19) Vidler, “Architecture and the Enlightenment,”188.

(20) Rousseau, A Discourse on Political Economy.

(21) Vidler, 189.

(22) Ledoux, 43.

(23) Ibid, 41.

(24) Ibid, 42.

(25) Vidler, 196.

(26) Ibid, 184.

(27) Hays, "Diagramming the New World," 240.

(28) Ibid, 243.

(29) Aureli, Less is Enough, 15.

(30) Aureli, "Theology of Tabula Rasa," 121.

(31) Hays, 240.

(32) Ledoux, 43.

(33) Aureli, Less is Enough, 15.

(34) Ibid, 16.

(35) Aureli, "Theology of Tabula Rasa," 121.

(36) Hays, 243.

(37) Ibid, 234.

(38) Ibid, 235.

(39) Ibid, 243.

(40) Rousseau, A Discourse on Political Economy.

(41) Meyer, Building, 117.

(42) Mertins, "Anything but Literal," 58.

(43) Hays, 246.

(44) Meyer, 117.

(45) Ibid.

(46) Hays, 247.

(47) Ibid.

(48) Meyer, 117.

(49) Ibid, 120.

(a) Landscape with a Youth by a Pond, Jean-Honoré Fragonard (c.1770)

(b) Perspective View of the Loue River, L'architecture considérée sous le rapport de l'art, des moeurs et de la législation, Claude Nicholas Ledoux (1804)

(c) Agriculture et économie rustique – batteurs en grange, Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates) (Paris, 1762)

(d) Lutherie – [2] Seconde suite, Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 5 (plates) (Paris, 1767).

(e) Co-op Zimmer, Hannes Meyer (1926)

(f) Still Life with Glass of Red Wine, Amédée Ozenfant (1920)

(g) Die Petersschule, Hannes Meyer (1926)

(h) Nature morte, Still Life, Le Corbusier (1920)

(i) bauen, Hannes Meyer (1928)

PART II

Vis-à-Vis

(Coming soon)

PART III

The Wicked Glazier

(Coming soon)